Is there a clear difference between the performance of Uruguayan players in their clubs and in the national team?

Introduction

Much has been said about the moment that the Uruguayan team is going through, with a change of DT included, and although practically half of my life was spent with Maestro Tabarez as coach of the team, I grew up under the phrase “These in their teams break it , they come here and do nothing”, the idea that gave rise to this post is to investigate whether there is a clear difference between the performance of Uruguayan players in their clubs and in the national team. As I progressed, I added another theory, the end of a generation of players.

First it is worth clarifying the concept of key pass, according to the Glosario Diario Marca, a key pass is anyone that leads to a shot on goal, regardless of whether it ends in a goal or not. While the value of Recoveries is calculated as the sum of the tackles won plus the interceptions.

The forwards: Luis Suárez and Brian Rodríguez.

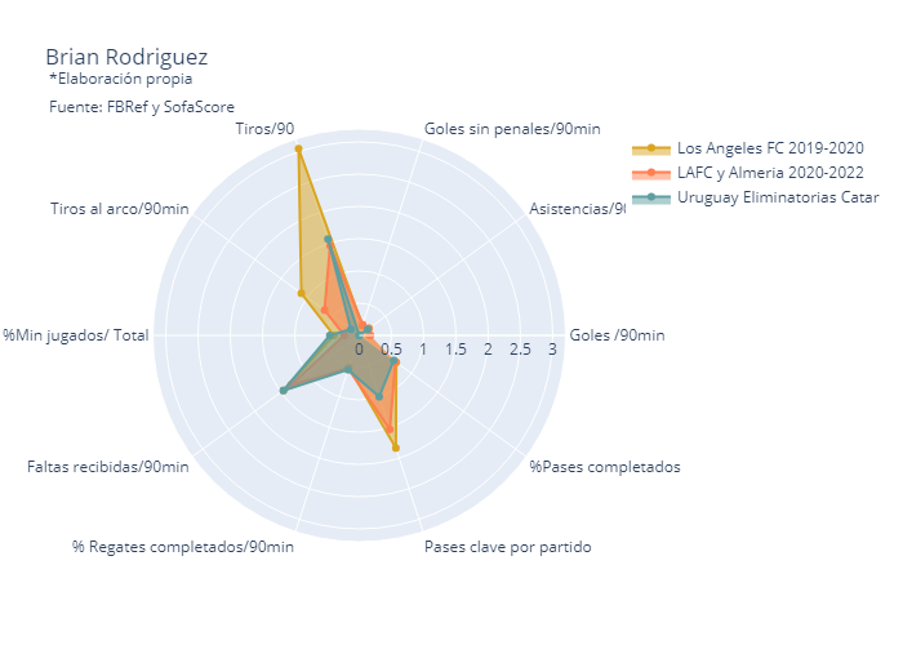

Brian Rodríguez

Although he is a player who is not called up for the double date against Paraguay and Venezuela, Brian shared a pair with Suárez for almost the entire tie, so we analyze how he performed at his club while the qualifiers were being played, and how he did over the previous years.

It should be noted that in the 2019-20 period his stay in Peñarol was not taken into account because he did not have the necessary statistics.

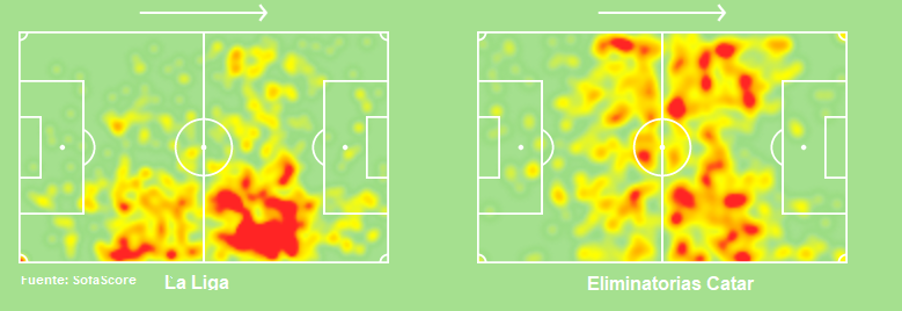

His speed and dribbling ability make him a constant victim of fouls, receiving a similar number of fouls per game as Suárez, giving the team set pieces. Despite this, we can see that Brian in his club has a greater offensive influence, generating more key passes per game and shooting in more opportunities, this creates a great contrast with his performance in the team with which he has not scored goals in the tie and has only one assist in 11 games. We can also see this difference in his location on the field, since in the national team he has hardly set foot in the area.

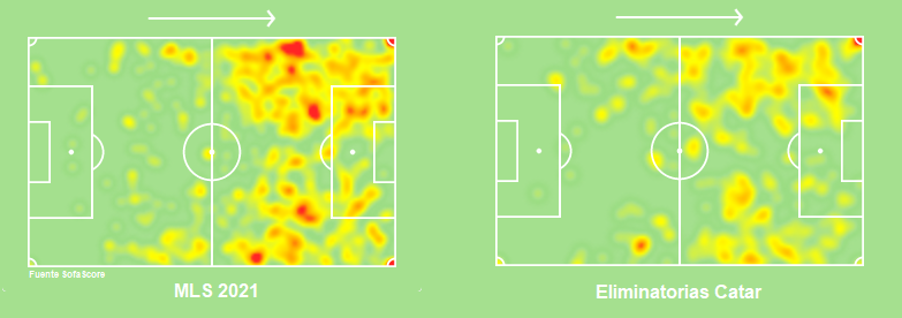

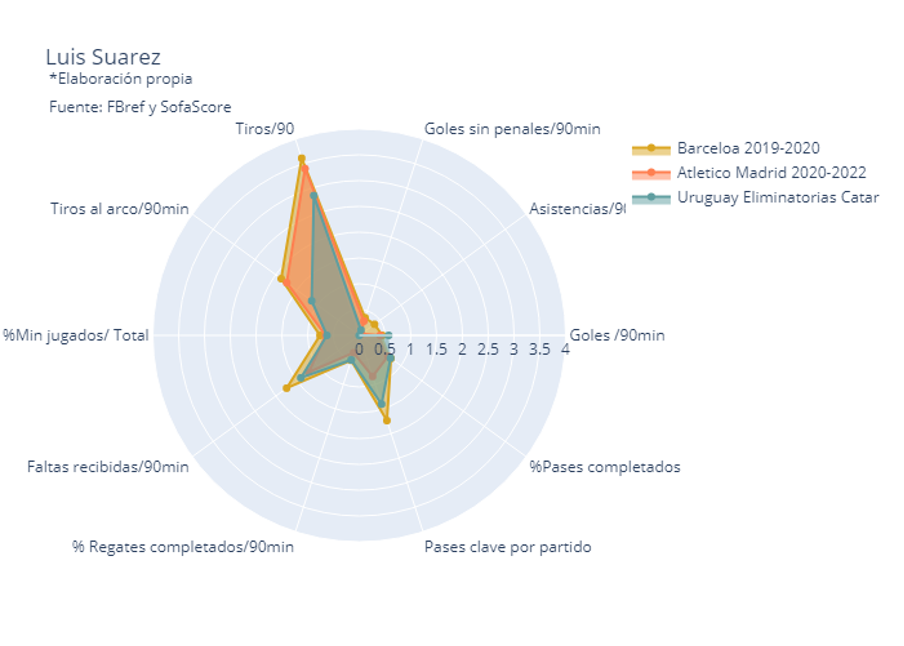

Luis Suárez

For many years we were used to having a 9 that, regardless of how the ball got to him, was going to put it away, but that facet of Suárez seems to have disappeared.

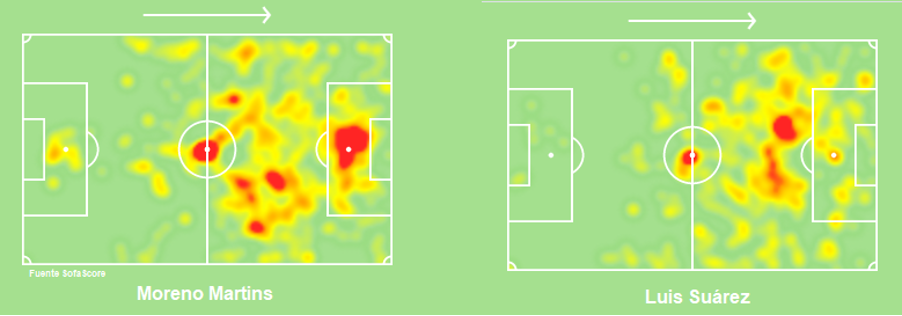

Although it is notorious that with Uruguay he does not have as many situations as he does with his clubs, looking at his heat map we can see that he is outside the box a lot of the time, although it is something that we can also see when he plays for his club, the presence in the area with the national team is on the penalty spot, this is the most worrying statistic, Suarez has not scored goals with a moving ball so far in the tie, four of his five goals have been from penalties and the remaining has been a free kick. In other words, if we remove his presence in the area by taking penalties, we see that our 9 is most of the time away from his area of greatest influence, the area.

In the tie he has shot an average of 2.5 times on goal per game, while Marcelo Moreno Martins, top scorer in the tie, has done so 3.9 times per game.

Comparison chart:

When comparing with Neymar, I don’t expect to compare the values of the Uruguayan forwards with the Brazilian star, but to serve as a guide when reading the radar, since Neymar has the best numbers in the competition in almost all parameters.

The midfielders: Nahitan Nandez, Matías Vecino, Rodrigo Bentancur and Federico Valverde

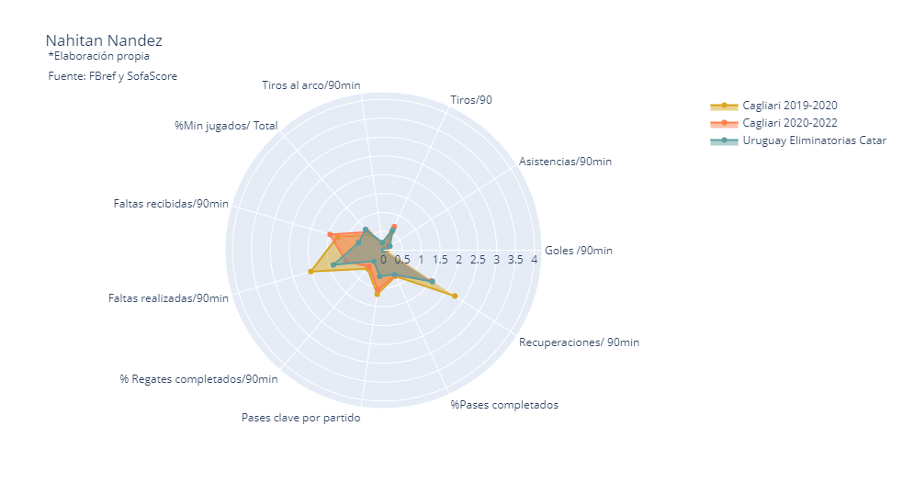

Nahitan Nandez

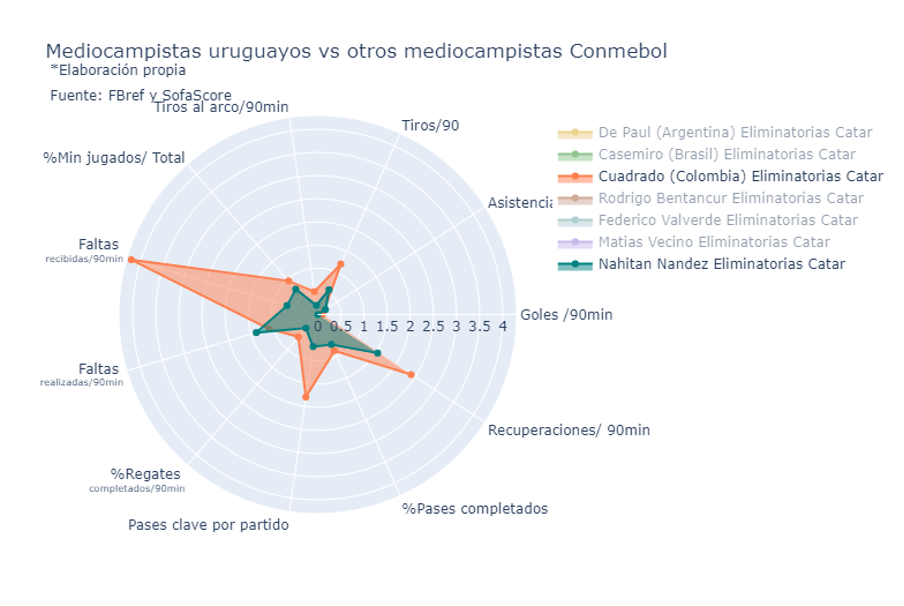

Nahitan is a player who is characterized by his dedication, to which he adds two assists in this tie, including a key for Pereiro’s goal, which is why it caught my attention that the data does not support his dedication What’s more, of the headlines it is the one with the worst numbers. This result contradicted my perception that he was an essential part of the team, the more it caught my attention that according to the SofaScore score, he ranks 31/32 among Uruguayan players with a score of 6.42 only surpassing Federico Martinez who has 13 minutes played in the tie. The data that I would have liked to have, and I did not find in the open statistics pages is the number of kilometers covered per game, it would contribute to the analysis of all the players but mainly in that of Nahitan.

This is a great example of how data sometimes gives us insight that clashes with our beliefs.

Rodrigo Bentancur

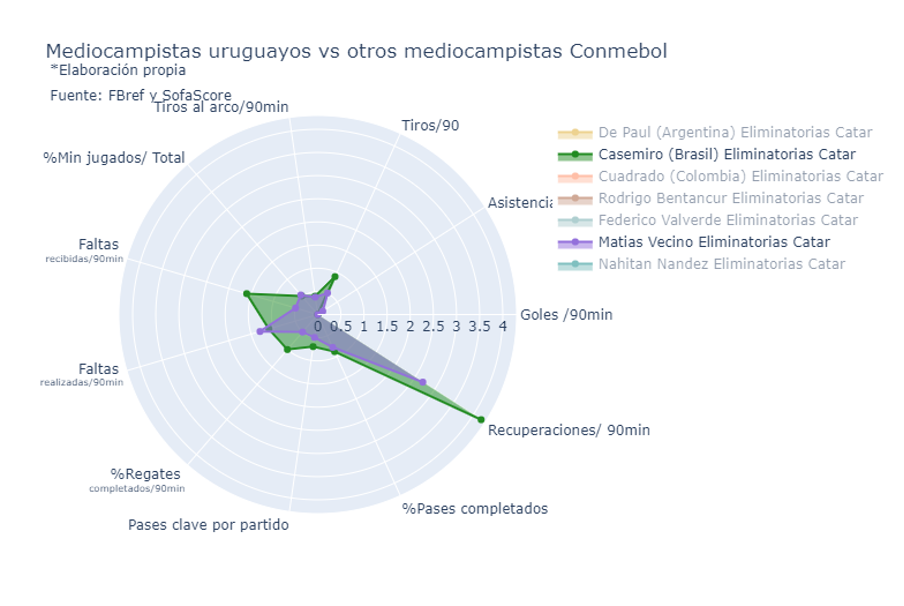

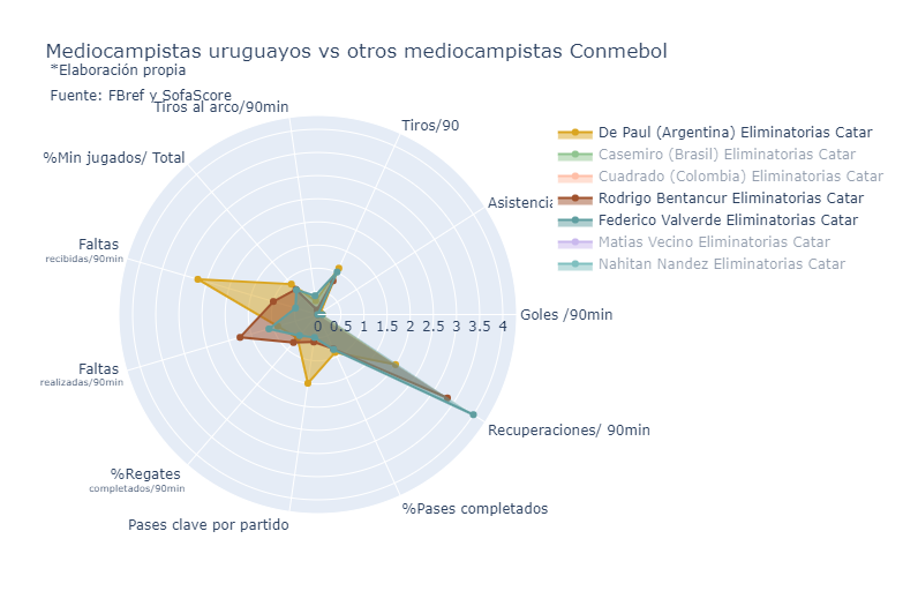

Bentancur in several aspects complies in the same way as he has done in recent seasons with Juventus, however there are two aspects in which he clearly fails to match his marks in Italy, the first is in recoveries, an aspect in which Valverde and Vecino improve his numbers with respect to his club, and the second is a problem shared by all Uruguayan midfielders and is that of fewer key passes per game.

Another factor to consider is how the area of influence of the player changes in his club and in the national team, in the latter he spends more time on the left side of the field. This also happens with Vecino and Valverde, players who tend to turn to the right and start playing in a different position in the national team. Neighbor like 5 brand, Valverde and Bentancur throughout the attack front.

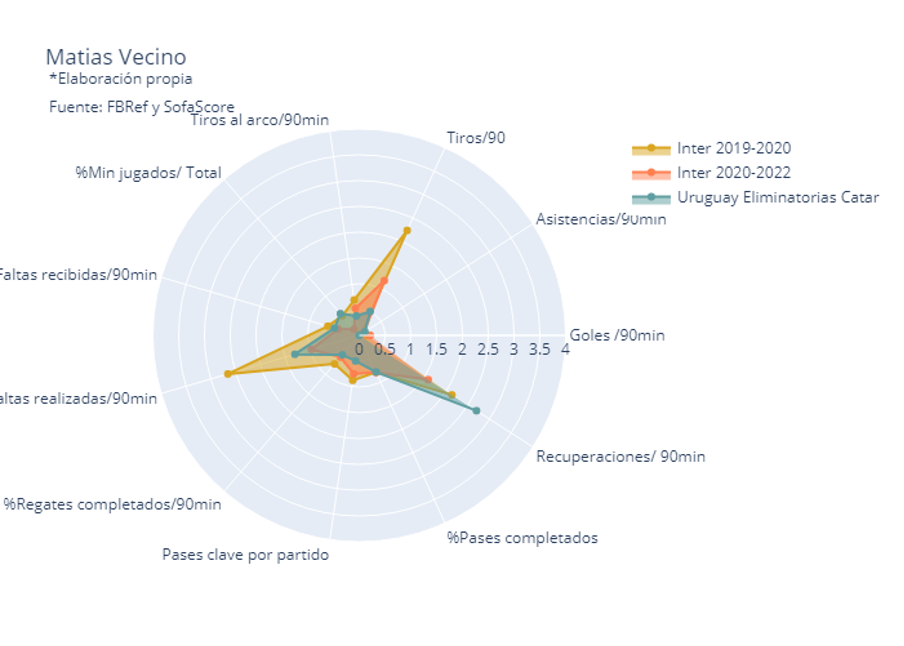

Matías Vecino

The first fact to take into account is the lack of minutes that Vecino has had in the last time at Inter, he went from playing half of the possible minutes with Inter to 15%, while in the national team he plays 55% of the possible minutes. This lack of minutes in his team is reflected in a clear decrease in several of the performance indicators in his club, which fortunately has not affected in the same way in the selection in which we see him in a more defensive facet, with fewer shots, dribbles and key passes but with more recoveries and almost twice as many clearances per game, this due to the change of position, while at Inter he focuses on the right side of the midfield, in the selection he is mostly located between the middle of the field and the last quarter of the field.

The map of previous seasons was taken since in the last ones he does not have enough minutes to make his position clear.

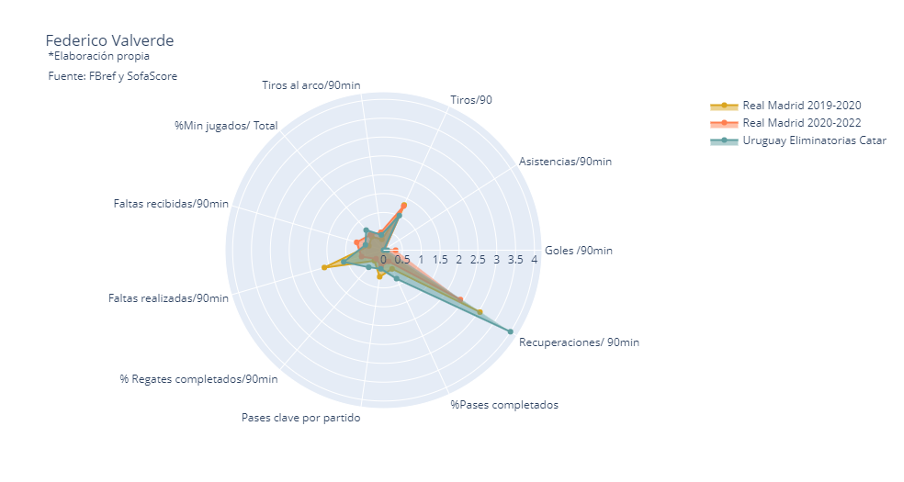

Federico Valverde

Having a player who plays for Real Madrid immediately makes us dream of playing like Real, although this is a long way off we can see how one of their players plays in Spain and how he does it for our team.

Unlike Vecino, Valverde is in a better moment in his team than in previous years but the differences between the performance in his team and in the national team comply with what we have seen in the rest of the midfielders, their defensive numbers improve but with this seriously compromises the offensive facet that these players show in their clubs. In the case of Valverde, it is added that he uses it in a position quite different from the one he fulfills in the national team, going from positioning himself as a midfielder on the right to covering the entire half of the field.

Comparative tables:

It is incredible that Casemiro has 100% of the successful dribbles, but it is worth clarifying that he only manages 0.4 per game against 0.2 for Vecino, Valverde manages 2 per game. This data is also related to the fouls received. If he didn’t need them, would he leave with the ball? I tend to assume that the phrase “pass ball or player” applies.

In the comparison of the most creative midfielders we see that ours have a better defensive performance, but that the Argentine surpasses them in a great way in offensive work, I did the exercise of comparing De Paul’s numbers against what Valverde and Bentancur do in their clubs, and coincides in various statistics with the latter (% Passes, Key passes, % Dribbling, Shots), especially in past seasons (2018-20) where both played in the same league.

As I mentioned in Nahitan’s section, I was surprised by the difference between my perception and the numbers, the difference is bigger if we compare him with a player who plays in his same position, who is also used to playing in all positions on the wing and who also plays in the same league. Another aspect to highlight is that the difference is not only offensive or defensive but the Colombian has better numbers in both aspects of the game.

The full-backs: Martin Cáceres and Matías Viña

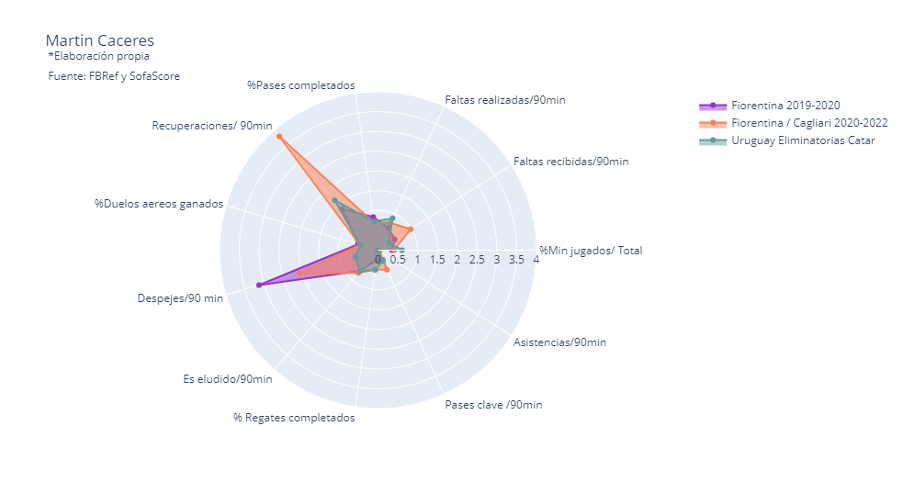

Martín Cáceres

The graphic of “Pelado” is one of those that a priori generates the greatest impact, especially in quick reading we see a huge difference in recoveries and clearances, and this is mainly due to his positioning on the court.

While at Cagliari he is used as a right-back, at Fiorentina he played on both flanks and even as a defender, so it is logical that his defensive performance indicators are notoriously higher at the club compared to those of the national team, another point that What is striking from the analysis of the heat map is that in the national team he plays much more advanced than in his club, or at least that he has less defensive participation.

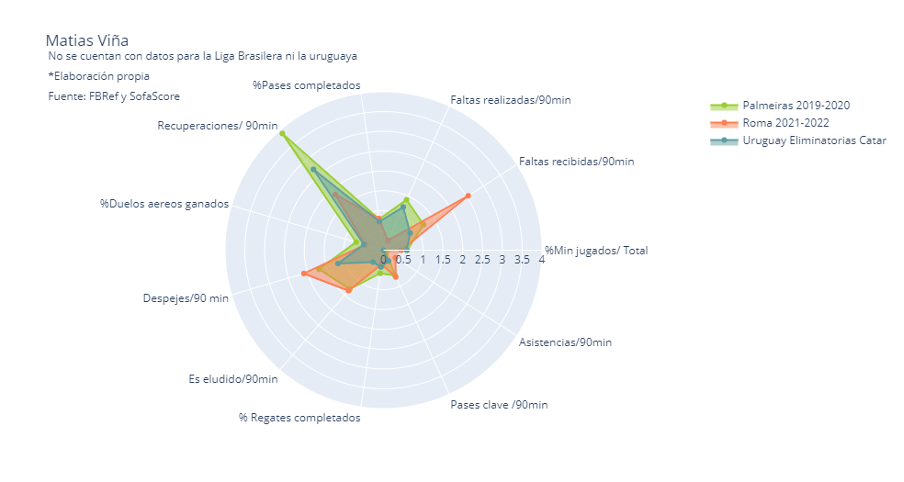

Matías Viña

Unfortunately, neither Brazilian soccer nor Uruguayan soccer have open statistics in StatsBomb to be able to fully analyze Viña’s passage in Palmeiras and Nacional, what I did in this case was take the Serie A data for the season from SofaScore 2020/21.

As it happened with several players, we see how some of the indicators of his offensive game decreased, but in this case we do not see a compensation on the defensive side, as the recoveries and clearances decreased, but one indicator that decreased and it is good news is the number of times he is eluded per game. It is worth clarifying that the tactical system in which Viña plays has changed, in Palmeiras and Uruguay they usually play with a line of 4 defenders while Roma has recently opted for a line of three, the decrease in the number of fouls committed and the increase in fouls received could be attributed to the change of position, but the heat map shows that he runs the entire wing.

As with Martín Cáceres, his absence in the last quarter of the field is striking, although Viña falls more than Cáceres. Another aspect to mention about the heat map is how in Uruguay he plays closer to the wing, delimiting his area of influence.

Despite the aforementioned, Viña has numbers in the national team comparable to those of Danilo with Brazil.

The defenders: Diego Godin and Josema Giménez

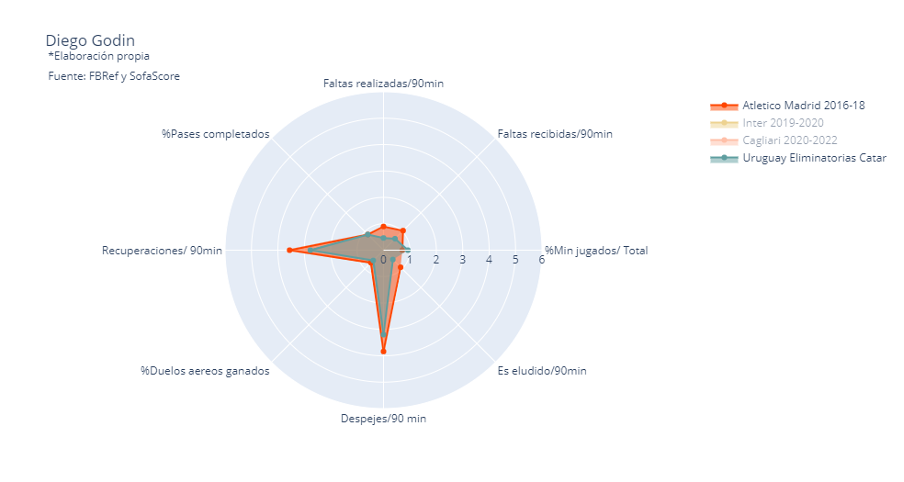

Diego Godin

The captain has been one of the players hardest hit by the recent results of the selection, due to the performance of Cagliari, a team that brings together three of the players analyzed. And although his loss of speed is notorious, it is not analyzable with the measures we selected, with these it can be blamed that he clears fewer balls in the national team than in his club or that the percentage of aerial duels won is lower (5 % approx) in the national team, but he is eluded fewer times and makes fewer fouls than he does in his club.

Just because he is the captain, I decided to take the years back a little further and compare it with his last time at Atlético de Madrid, where no one would have thought to question him.

And although he recovered a third more balls per game, and cleared 20% more, now he is eluded almost half the time. Another fact to take into account, and this can serve both as a defense for Godin and as an argument for those who are already looking for his replacement, is that from September to December 2021, he was injured three times, for a total of 45 days and missed 10 Cagliari matches according to Transfermarkt.

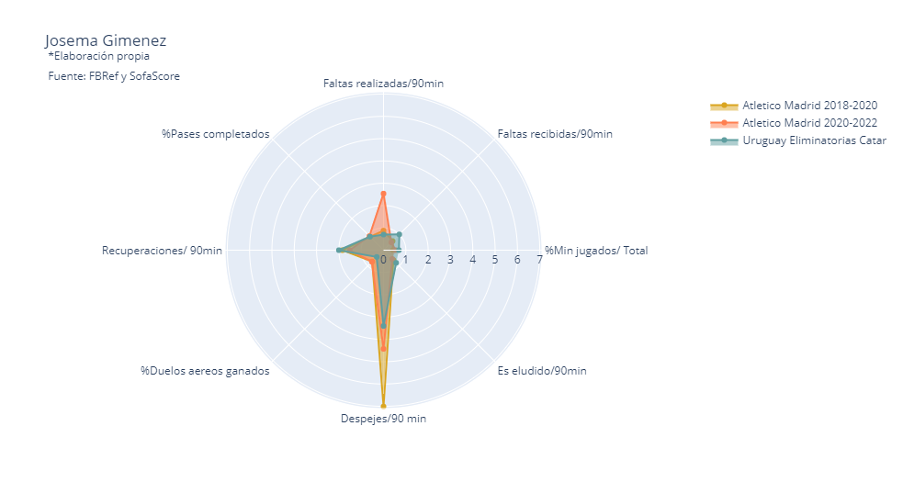

Josema Giménez

As the Atlético anthem composed by Sabina says: “Que manera de subir y bajar de las nubes. Qué viva mi Atleti de Madrid (What a way to go up and down from the clouds. Long live my Atleti de Madrid)“, in what appears in red under “Atletico Madrid 2020-22” we have two very different campaigns for Atleti, on the one hand one that comes out champion and another that has it fourth closer to tenth than first. This uneven behavior of Atleti makes the average for those years seem lower than the two previous years.

On the other hand, the enormous number of clearances every 90 minutes that Josema achieved in the 2018-20 period also gives us the feeling that there was an abysmal difference between those years and the others analyzed, despite that, there is also a considerable difference in recent years in clearances with Atlético de Madrid and with Uruguay, this difference reaches almost one clearance per game.

Another very striking point has been in the percentage of aerial duels won, at Atlético Madrid it is around 70% while in Uruguay he only won 43%, to which we must add that Godin at this point went from 60% to 55 %.

Player comparison:

Comparing our defense with Yerry Mina, we notice that we are even on several points, our defenders having better values for certain points, but there are two that the Colombian defender has a clear difference, on the one hand the percentage of aerial duels won where he gets a 10 % advantage over Godin and more than 20% over Josema, and another enviable difference in the number of times he is eluded per game, where Mina has 0.1/game while Godin 0.5 and Josema 0.8.

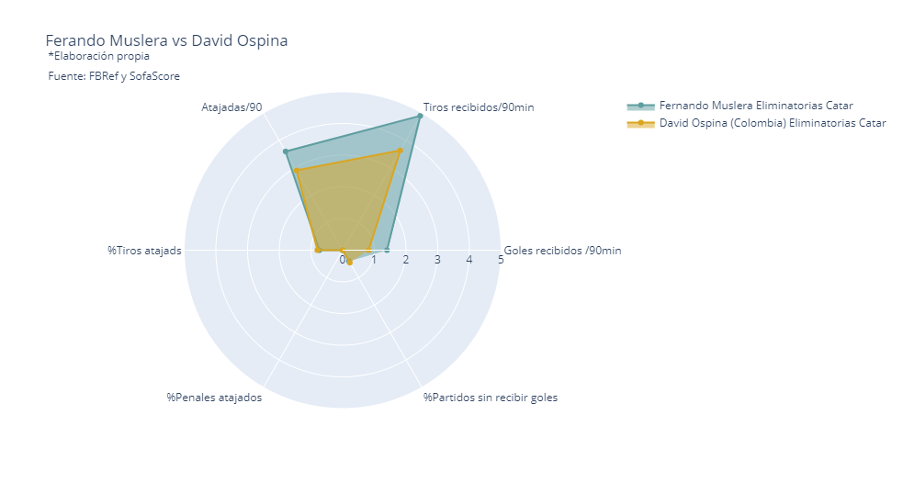

Goalkeeper: Fernando Muslera

Muslera has been in the eye of the storm lately, with some goals that we all believe to be avoidable, especially goals that put the game 1-0, the goalkeeper has managed to overcome those goals but the team has not gotten back into the game.

Muslera has saved 72% of the shots that have gone to the national team’s goal, while at Galatasaray he has been around 78%. But both in the graph compared with Galatasaray and with David Ospina (80% save), the Uruguayan defense does not help him enough, since he has received approximately one and a half more shots per game compared to what Ospina receives in Colombia or what he received during 2020-22 on his team.

The only goalkeeper who received more shots per game than Muslera (4.9) was the Bolivian Carlos Lampe (5.71).

Conclusion:

Despite the fact that several players take a greater role in the defensive part compared to their teams, we are one of the teams that receives the most shots on goal and the third team that conceded the most goals in the tie (21 goals) behind Bolivia and Venezuela.

On the other hand, we saw that all Uruguayan players suffer a drop in their key passes and in the shots they take, these two measures are related to each other. Uruguay is the third lowest scoring team in the tie (14 goals) being only behind our next rivals Paraguay and Venezuela. This goes hand in hand with the fact that all Uruguayan forwards and midfielders shoot fewer times on goal in the national team than in their clubs.

This puts us in a weak position where we are a team that finds it hard to reach the opponent’s goal, that has few chances per game and that in turn receives a large number of attacks, especially if we compare it to the rivals with whom we are playing for qualification.

Regarding the triggering idea of the post, to see if “their clubs play better”, we cannot say that there is a noticeable difference between their performance in their clubs and in the national team analyzed in the period in which the tie was played, if it is true that in several cases in the seasons (2018-19, 2019-20) vs (2020-21, 2021-22) several players saw their level decrease in the last two years compared to the previous two years.