HUNDRED – HOGUE’s latest book

In 2020, a year which will be remembered in history as the year of the Great Pandemic, Quanam sponsored the edition of the book HUNDRED, Fifty & Fifty by artist Horacio Guerriero (Hogue). While Hogue has travelled varied paths in plastic arts, he has felt at ease in caricature.

Throughout history, major artists cultivated and transformed a cartoon into a higher artistic form, such as Honoré Daumier, Goya, Monet, Toulouse-Lautrec, and Gustavo Doré, among others. In Uruguay, there have been brilliant cartoonist too, and I will take the liberty to mention solely the artists that I have personally met.

The first was Julio Suárez (Peloduro). I was a kid, my father and I were in a bookstore, when the artist walked into the place. “Come, I’ll introduce you to him, “said my father, “he’s from Salto Province, like me.” Then they talked while I listened to their conversation.

The second one I met was Hermegildo Sabat (Menchi). I met him at his parents’, Juan Carlos Sábat Pebet and Matilde Garibaldi, who very generously hosted members of the Uruguayan Centre for Past Studies. Historian Flavio García, alma mater of the Centre, attended the meetings and then he would invite my wife and I, when we were young newlyweds.

Francisco Graells (Pancho) and I are from the same generation. We met in Uruguay, during the hectic 60s. Later, every now and then, we kept in touch, either in Montevideo or in Paris. We even worked together when the 24th Latin American Congress of Psychoanalysis took place in Montevide. On that occasion, Pancho made the graphic image of the Congress, and I managed to have issued, a commemorative stamp of Uruguay, one of the few that bear the image of Sigmund Freud in the world.

All three engaged in caricature, and usually published in daily and weekly newspapers, and magazines. We can easily recall Peloduro in Marcha (Uruguay), Menchi in Clarín of Buenos Aires, and Pancho in Le Monde, in Paris.

It is an extremely stressful job: they are daily expected to come up with a cartoon portraying the situation or the character of the moment. Cartoon subjects must be recognizable and have a gist of humour to bring a smile to the reader or make them snort.

These experiences lead me to Hogue. He is somewhat younger than me, and we met by friends in common, and because I attended all his exhibitions. Fifteen years ago, my daughter Julieta graduated as a Medical Doctor, and it occurred to me that Hogue could make a caricature of her.

It would be a memento of that central event in her life, and in ours as a family. My wife Moti and I met him at “4 Ojos” [4 Eyes] to make the order. Sometime later, he called us to get together to see his work. He had prepared not one but two caricatures which we so much liked that kept both.

One was framed and we gave it to Julieta on her graduation party; the other, together with an allusive poem by Pablo Neruda, was printed on book markers which we distributed among the family and friends who joined us in the celebration.

I am not going to talk about Hogue’s art. Art in general, and painting in particular, is not explained, it is felt. And the plastic arts, as well as the music, provoke and give rise to many feelings and interpretations. I am just going his to wonder why Hogue called his book HUNDRED. Fifty & Fifty.

There is a pseudo-science about the meaning of numbers, which dates back so far, it reaches mythical times. For example, it is known that 666 is the number of the Beast (or the Devil, or the Antichrist), because the Book of Revelation of St. John says so in the Bible.

Closer in time, our National Directorate of Lotteries and Pool Coupons, has made available a list of dreams with their corresponding numbers. However, numbers range from 00 to 99 but 100 is not on the list. I remember that when I was a child, I knew that 03 was Saint Cono and 48 “il morto qui parla”.

Clearly 100 is linked to the decimal system (10 times 10, or 10 squared), which must have been created because a man has ten fingers in his two hands and learned how to count on them. 100 appears on numerous occasions: the first 100 days of a new government, Napoleon’s 100-day campaign ending in Waterloo, the 100-year-old war between France and England, Gabriel García Márquez’s 100-year-old solitude, the 100 neighbourhoods of “Buenos Aires (“Porteño”)” tango, and back to the Bible, Abraham was 100 years old when his son Isaac was born. This last example might be showing us that 100 is a number that symbolizes that seemingly impossible ventures, may not be so.

At the beginning I referred to the year Hogue published HUNDRED. Year 2020 will never fall into oblivion; the year of the Great Pandemic of COVID-19 will go down in history as another unforgettable year. Just to name a few, the year of Christ’s birth is not only remembered, but taken as a time reference in our civilization as BC and DC, meaning before and after Christ.

As to pandemics, the worst pandemic Europe went through was the black death (or bubonic plague) between 1347 and 1353. It is estimated that population then, was reduced by 40% to 60%, meaning from 80 million to approximately 50 or 30 million people.

Two hundred years later, in 1562, the oil of Pieter Brueghel the Elder “the Triumph of Death”, evidences the deep imprint that epidemics and wars had left in Europeans’ memory.

It is interesting to provide some data from the 1918-1920 influenza pandemic, also known as Spanish Influenza. It was a pandemic caused by an outbreak of H1N1, a subtype of influenza virus type A. Unlike other flu epidemics which mainly affected children and the elderly, their victims were also young and healthy adults. This pandemic infected a third of the world’s population and killed at least 50 million people, including high infant mortality and healthy people aged between 20 and 40.

Here comes HUNDRED again: it is the number of years that separate the Spanish Influenza pandemic from that of COVID-19.

David Quammen[1], very briefly explains how different the situation was then: “At the time of the1918-1920 pandemic, no one knew what was causing it (although there were many conjectures). No one could find the bug causing it, no one could see it, no one could name or understand it, because virology itself had barely begun to exist. Viral isolation techniques had not yet been developed. Electronic microscopes had not yet been invented. The responsible virus, which turned out to be a variant of H1N1, was not accurately identified until. 2005!”.

There is also a connection between HUNDRED and 2020. 20 is the basis of another numerical system: the vigesimal system, which is still in use in some places. Same as 10, the vigesimal system must have originated because a man has ten fingers in his two hands, and ten toes. For example, in French, 80 is not “octant” but “quatre-vingt” (four twenty). The vigesimal system is used in other languages such as Basque, Celtic, Danish, and even English, where people have historically counted in twenty, scores. The former British monetary system had twenty shillings per sterling pound.

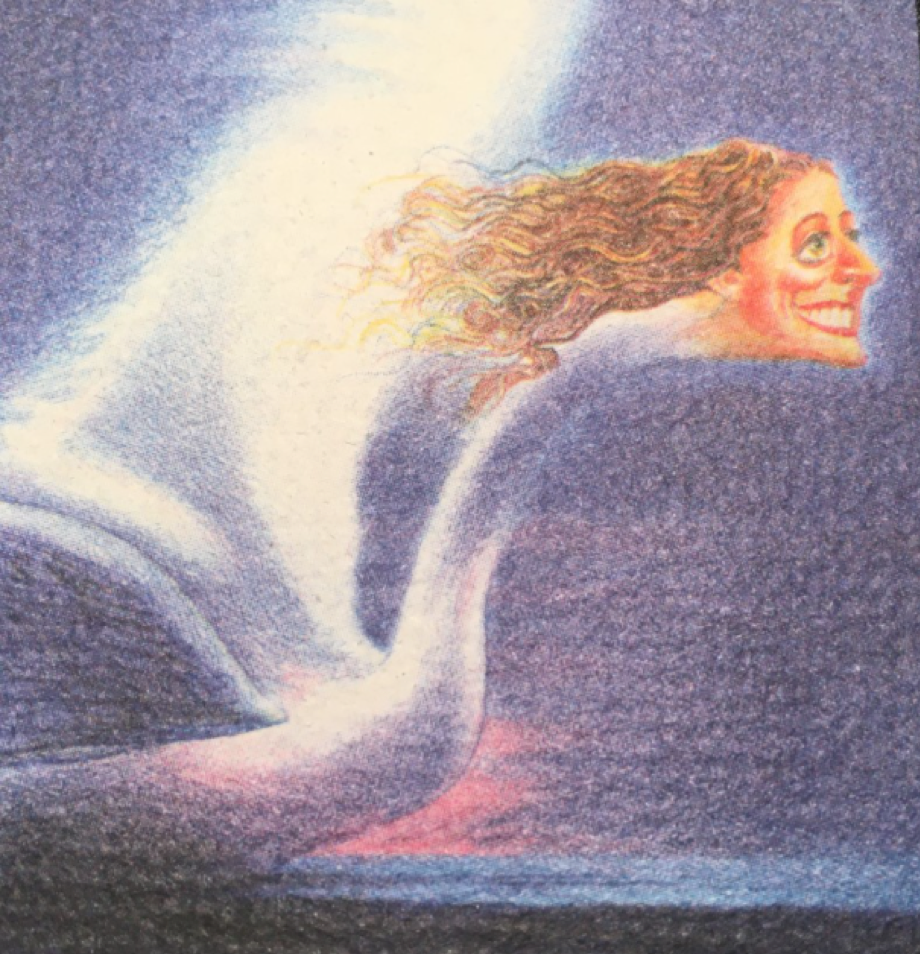

There is another feature in Hogue’s book title: HUNDRED. Fifty & Fifty which we have not referred to yet. The second part refers to the contents of the book: fifty cartoons of characters and their fifty quotations. But why in English? At first, I thought that it could have been “Medio y Medio”, each half of a page shows a character, and the other half, a text. Moreover, “halves” are not new in Hogue. In his last exhibition in 2017, AnimalES (AnimalS), the characters portrayed were half human, half animals; half real, half dreamlike.

But why in another language? I dare suggest that it is because English is the global “lingua franca”, especially after the end of World War II. This was anticipated by the Iron Chancellor, Otto von Bismarck in 1898; when he was old, a journalist asked him what he considered the decisive factor in modern history would be. He said, “The fact that Americans speak English.”

How the world changes in just 400 years. In the sixteenth century, the polyglot emperor of the Holy Romanesque Germanic Empire Charles V, also Charles I king of Spain, whose Habsburg empire was not born from military conquest but out of marriage, assembled by a series of cunning marriage alliances, declared the following, where English is absolutely ignored:

“I speak French with men, Italian with women, Spanish with God, …and German with my horse”.

Finally, I quote from an apocryphal letter by F. Scott Fitzgerald, his words on his supposed quarantine during the Spanish Flue:

“Officials have alerted us to make sure we have the necessary provisions for a month. Zelda and I have stocked up on red wine, whiskey, rum, vermouth, absinthe, white wine, sherry, gin and, if we need it, brandy. Please pray for us.”

[1] “Spillover: Animal Infections and the Next Human Pandemic”, W. W. Norton & Company, New York, 2012

Ing. Víctor Ganón

founding partner of Quanam